Look, it's a pretty decent book trailer!

In 1914, Europe teeters on the edge of an all-encompassing war. Alek, a Hapsburg prince, is a "Clanker"--the term for people whose technology is reliant on machines. Deryn, a girl just inducted into the British Air Service, is a Darwinist--those who develop animals into their technology (clearly they're the good guys). Alek and Deryn probably would never meet under normal circumstances, but with a war going on anything can happen.

I normally steer clear of novels with the premise of

Leviathan, but when I read

Lusty Reader's great review of

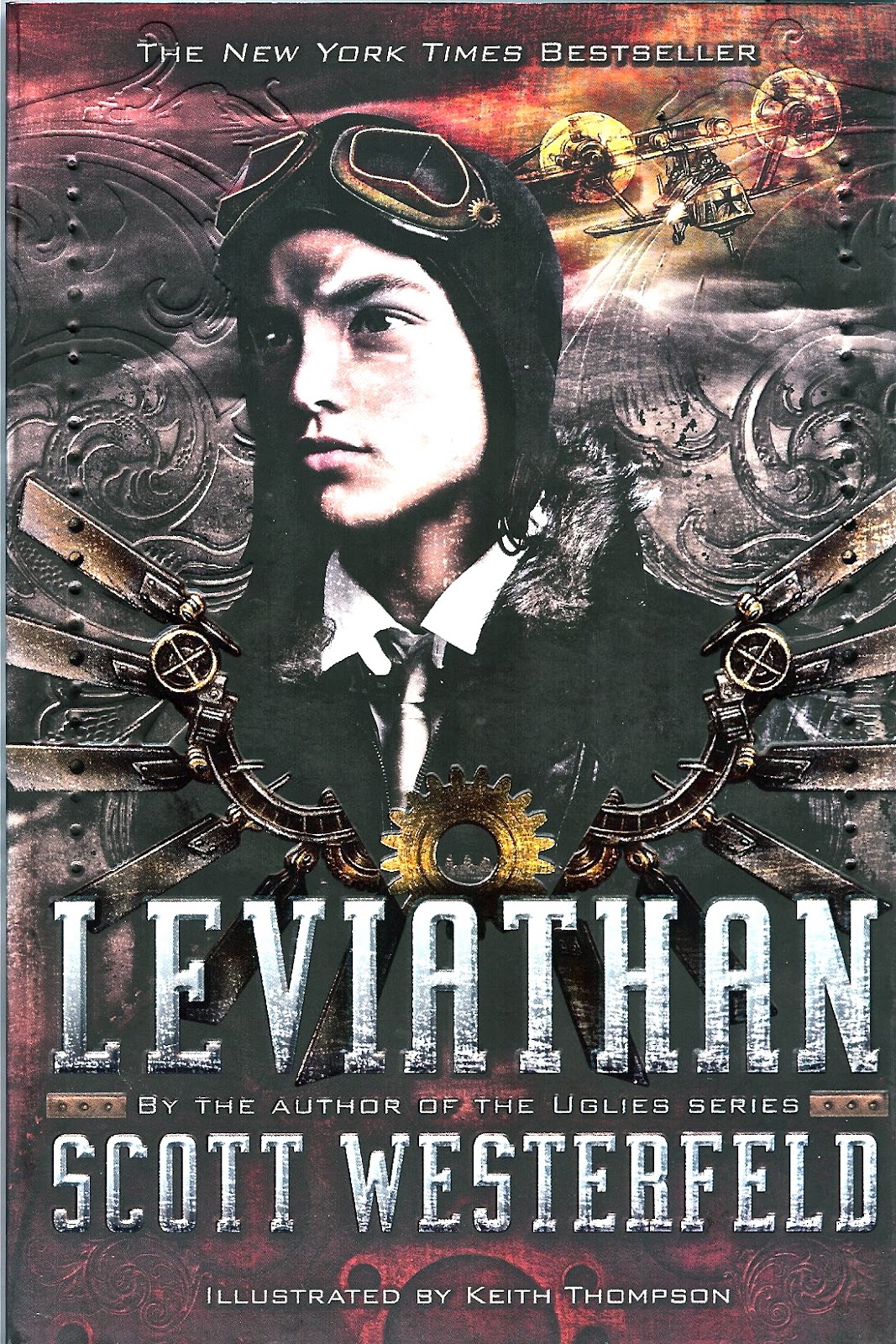

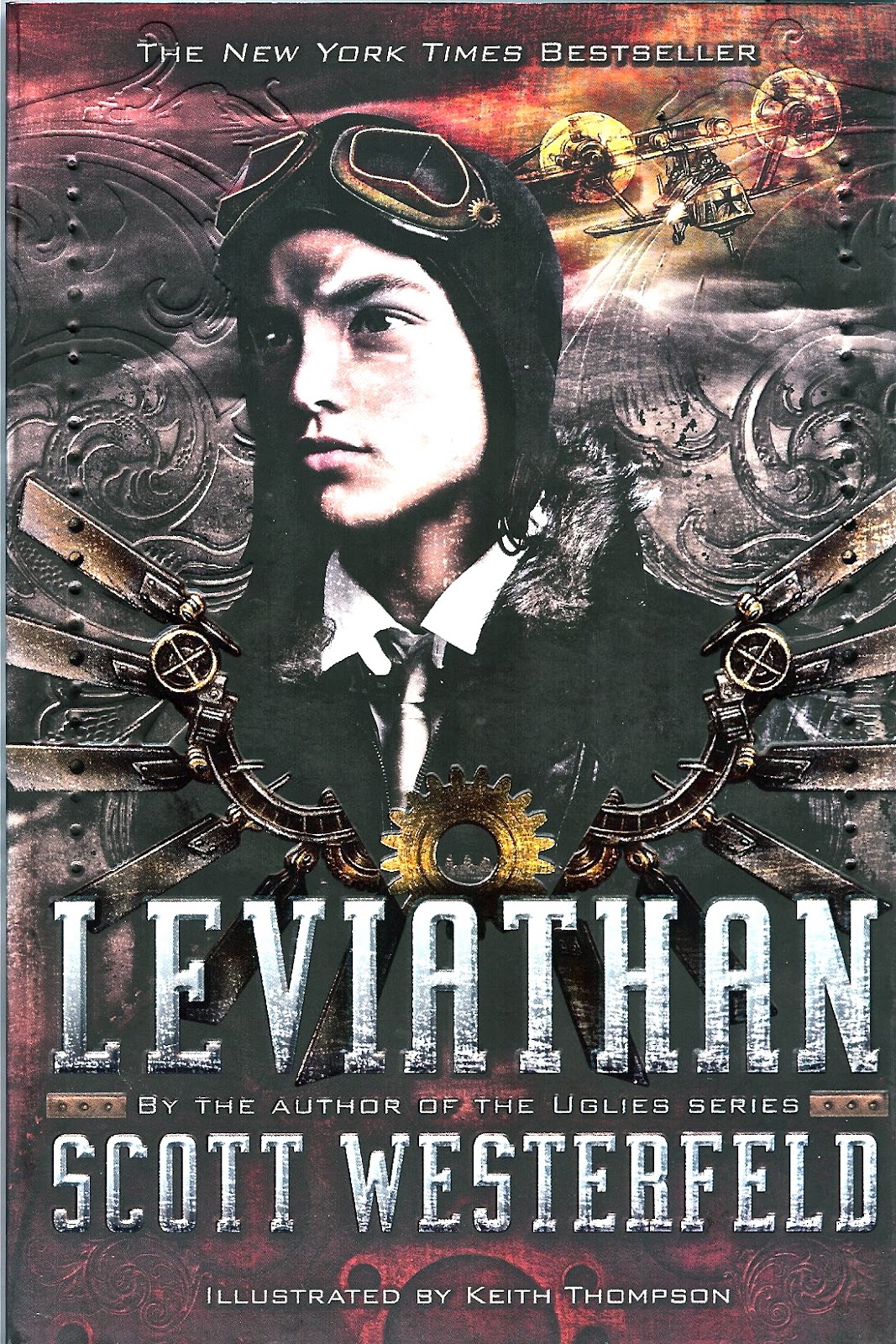

Goliath, I decided to give it a try, since I know we tend to love the same books. First of all, I have to say that as a physical object

Leviathan is gorgeous--great, tactile cover, lovely thick paper, and lots of illustrations (have I ever mentioned I LOVE books with illustrations?). On top of that, it tells an awesome story. Yes, there were some battle scenes that started to feel a bit long-ish, but for the most part this is the type of novel that feels like it's going by really fast. I'm not sure I would say it was unputdownable, but it was pretty engaging.

That being said, I feel like I enjoyed

Leviathan despite my better judgment, because it's kind of sexist. I already touched on this a bit in Fun with Gender Stereotypes (post

here), but that was really just the tip of the iceberg with this novel. In this entire book there are only two women. TWO WOMEN. IN THE ENTIRE WORLD of this story.

That. Is ridiculous.

Now, one might say that since the book is set during WWI and takes place largely on an airship, this makes sense. But that is such a cop-out response. Firstly, this is a fantasy version of WWI, so

Scott Westerfeld could write women into the armed forces if he wanted; other steampunk authors have done so. Secondly, in real life there were thousands of women involved in WWI, so including them would actually be more historically accurate than not. And thirdly, although much of the book does take place in a military setting, there are a few civilian scenes, and there are no women there, either! When Alek visits the German village, all the people he takes note of or interacts with--even just to buy a paper--are men. The same is true when Deryn is in Regent's Park--aside from the lady boffin, the other female character in

Leviathan, all the people doing anything worthy of description are men.

So, as far as the reader is concerned, the only two females who are physically present in the world of this book are Deryn and Dr. Barlow (both Deryn's and Alek's mothers are mentioned, in that they have mothers--obvs. But Deryn's mother is mentioned in passing, exists only off-page, and exerts zero influence on the narrative; the same is true for Alek, whose mother is killed before the book even starts. Compare that to both of the main characters' fathers, who exert a very strong influence on their decisions in the story and, while existing off-page, are both more fully realized characters). Once again I have to say: two whole women in the entire continent of Europe, really?! And let's take a look at these women.

First and foremost, we have Deryn, who is pretending to be a boy named Dylan so she can serve in the British Air Service. The BAS doesn't allow women, apparently. While I understand that

Westerfeld might have wanted to give her a secret for narrative purposes, it doesn't feel fully realized. Deryn doesn't stew over inequality based solely on gender, has no qualms over how she's going to hide things like her menstrual cycle, or considers alternative where she doesn't have to lie and pretend to be a boy. And while she fits in with the crew with astonishing ease, there are still broad statements about gender that seem pretty sexist. For example, the only thing Deryn dislikes about hanging with boys 24/7 is that they're super-competitive. Really? Because girls aren't competitive? How many women did you spend time with back in Scotland, Deryn?

Thirdly, Deryn's status as a strong female character derives entirely from the fact that she's pretending to be a male. She wouldn't even BE in this book if she wasn't pretending to be a boy. The reason why we think of her as a "strong female" is basically because she looks and acts like a boy. So basically erase every speck of femininity you can and you'll be a strong woman? Nice one.

Secondly, there's Dr. Barlow. While Dr. Barlow makes no secret of the fact that she's a woman, Deryn makes a big deal out of noting how unusual it is for a woman to hold Dr. Barlow's position as a prominent boffin, or scientist. And how did Dr. Barlow come by such a career? Why is she so well-respected? Is it because she's intelligent, has worked her ass off for years and demands people's respect? Is it because she sacrificed a personal life and family for her career? NOPE IT'S BECAUSE SHE'S RELATED TO A FAMOUS MAN. Seriously, that is the only backstory we're given--or apparently need to know--about the only other woman in

Leviathan.

The sum being that our two female characters have gotten where they are in life--which is to say, worthy of the notice of a story--by hitching a ride on the penis train: either by being more or less male, or by virtue of their fathers. Nice. Sorry if you have a vagina, kids, better luck next time! Just resign yourselves to a completely powerless existence without any autonomy now and make it easier on yourselves. I suppose technically

Leviathan passes the Bechdel Test, because Dr. Barlow and Deryn do discuss beasties and not men on a few occasions; but I'm not sure it counts if, as far as Dr. Barlow is concerned, Deryn's a male.

Obviously I'm not the target audience for this novel--that would be teenage boys, to state the glaringly obvious--but I was a little taken aback by some of the sexiest assumptions running through

Leviathan. So even though I did enjoy the story, and want to find out how Deryn and Alek are going to get together, I can't help but feel ambivalent about it.