Sometimes I have things to say about the books I finish, but not enough for a whole blog post. Enter mini-reviews! This time I focus on two recent non-fiction reads: Real Food/Fake Food by Larry Olmsted, and But First, Champagne by David White. I think both are valuable and worth reading, depending on your interests. Keep reading to find out more.

Real Food/Fake Food: Why You Don’t Know What You’re Eating and What You Can Do About It by Larry Olmsted

I like torturing myself by watching documentaries and reading books about how terrible American food is. Everyone needs a hobby I suppose. Anyway, I learned a lot from this book, such as:

- The difference between the US Department of Agriculture and the US Food & Drug Administration. The USDA is actually designed to serve companies and producers, while the FDA is supposed to protect consumers. However, the USDA is actually the more trustworthy of the two for consumers because the FDA is a useless trash fire that doesn't even bother to follow the bare minimum of its own internal policies, let alone regulate the shit other people do.

- What kobe beef actually is–I'd been looking into this before the trip to Japan, so I was surprised by how everything I read, on the internet or otherwise, was WRONG. Kobe beef is actually a genetically pure strain of cow from a very specific part of Kobe, and the genetics are what gives it its marbling and flavor, not massages and classical music and a diet of beer, as you might have otherwise heard. Also, only 3 restaurants in the US serve actual kobe beef. Everything else is fake.

- Speaking of restaurants, I had no idea restaurants could essentially call food anything they like, even if it's completely incorrect.

- The term méthode champenoise is not synonymous with méthode traditionnelle or méthode classique and can only be used for champagne, not other kinds of sparkling wines. That's because the "méthode champenoise" begins long before the wine is ever bottled and involves what grapes are grown, where, when, how they're planted, how tall they get, when they're harvested, and everything else that's part of the regulations for the winemakers of Champagne.

- I already knew that the olive oil industry was filled with completely fake products and that Italian extra virgin olive oil especially was to be avoided. But I didn't know that the best EVOO to buy is from Australia, which has the strictest regulations regarding olive oil on the planet.

Sometimes Olmsted takes the whole "fake food" thing a little far, like when he complains about Cook's labeling their wine champagne. I mean, it should really be obvious that Cook's isn't from Champagne, based on the price alone. But then maybe to some people it isn't so obvious, idk. Either way, I came away from this book with some great tips on how to read labels and what to look for to make sure I'm getting the most value for my money by buying "real" food.

But First, Champagne: A Modern Guide to the World's Favorite Wine by David White

I enjoyed the first few chapters of this book, which were engaging and well-written. When White got into the modern history of Champagne, however (namely the World War periods), it became sleep-inducing.

I also occasionally felt like White was either soft-pedaling certain facts to make the Champagne houses look good, or didn't bother to do his due diligence in his research. For example, take this passage from the beginning of Chapter Six:

Jay-Z and other celebrities abandoned Cristal after Louis Roederer's president, Frédéric Rouzaud, spoke dismissively of his new devotees.

This sentence makes it sound like Jay-Z and a few of his friends threw a fit because Rouzaud wasn't star struck. The truth is bit more complicated than that. In actuality there was an organized boycott of Cristal in the hip-hop community because they felt Rouzaud's comments were racist, or at least inspired by racism. (Fun fact: the sudden popularity of moscato in the late '00s and early '10s was thanks to this boycott. Jay-Z may have replaced Cristal with Ace of Spades, but most hip-hop artists decided to abandon champagne altogether and instead started drinking moscato.)

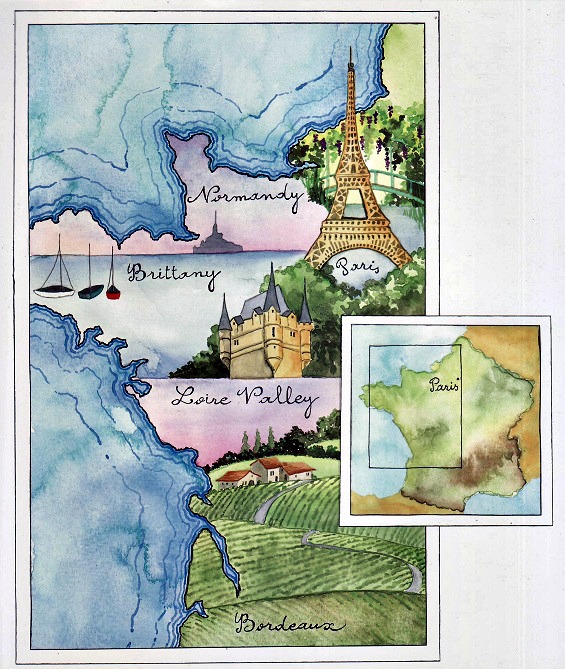

I certainly don't know even one tenth of what White does about Champagne, but in the small parts where I did know something, it seemed like White's information was either incomplete or not entirely accurate. That said, I did learn some stuff, the full-color illustrations were fantastic, and it's true that there isn't a book similar to this one on the market. If you're interested in Champagne, or if you're planning a wine tour of the region, this is a good place to start.

Discus this post with me on Twitter, FaceBook, Google+ or in the comments below.

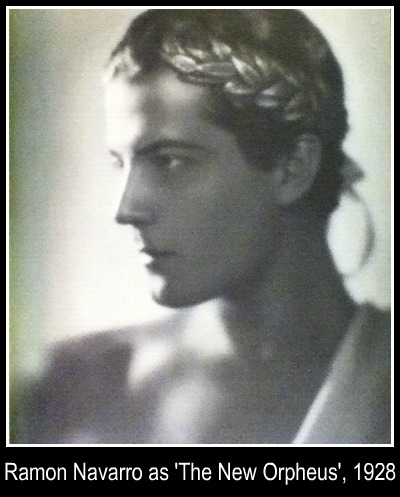

Johnny Weissmuller, photograph by George Hurrell, 1932

Johnny Weissmuller, photograph by George Hurrell, 1932 Tallulah Bankhead, photograph by George Hurrell, 1936

Tallulah Bankhead, photograph by George Hurrell, 1936 Anna May Wong, photograph by George Hurrell, 1938

Anna May Wong, photograph by George Hurrell, 1938 Veronica Lake, photograph by George Hurrell, 1941

Veronica Lake, photograph by George Hurrell, 1941