When people think of Hollywood's "Golden Era," images of beautiful actresses and formidable leading men captured in a black-and-white that seems sharper and more brilliant than any color film dominates in one's mind. To a great extent, the definable "look" of Classic Hollywood is attributable to one man: photographer George Hurrell.

In this book, film scholar and photographer

Mark A. Vieira discusses Hurrell's career and photographic techniques from 1925 to just before WWII. The book isn't as scholarly--or gossipy--as

Sin in Soft Focus, also by Vieira, but it is the best book book about Hurrell that I've encountered so far. It's true that Vieira doesn't break a lot of new ground here (most of the information he gives about Hurrell's encounters with Hollywood's famous stars and his technique can be found in

Hurrell Style), but he does present what he wants to discuss in a very readable and accessible writing style. There are several themes running through the book, but Vieira isn't heavy-handed with them, and for the most part this is a straight-forward mini-biography of a photographer. Also, the pictures in this book are

very well-chosen to both illustrate the text and demonstrate the best of Hurrell's technique.

Hurrell's Hollywood Portraits sketches the story of an artist always impatient and on the move--Hurrell rarely stayed in one place more than two years before boredom had him dropping everything and moving on to something new, and that included college. Whitney Stine described Hurrell as a painter who turned his hobby of photography into a chance career; but the fact was that even though Hurrell went to school to be a fine artist, he had years of experience working as a retoucher and portrait photographer in Chicago. Even though he kept painting throughout his life, by the time he moved to California in the 1920s, he knew painting was too slow a process for him to make a career out of.

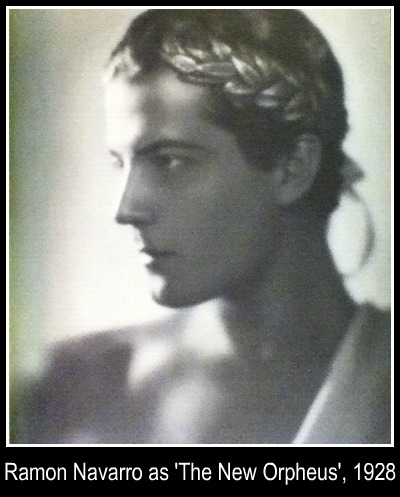

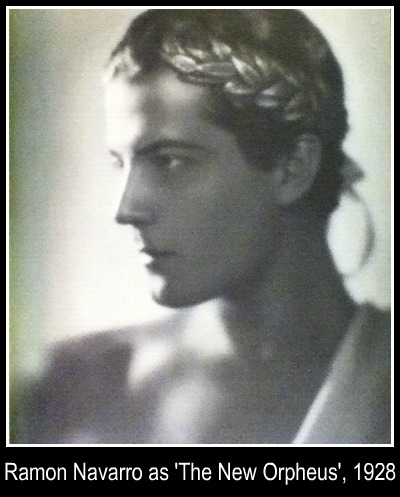

Please note this caption contains a typo; the subject's name is spelled Novarro.

The distinctive "Hurrell style" was characterized by sensuality, what Vieira calls an "almost-scientific" clarity, and abstraction achieved through unique lighting and framing of his subjects. When Hurrell started in photography, portraits where based on paintings (logically enough) and were very stiff and posed. They were also typically in soft-focus: the popular photographic style at the time was

pictorialism, also known as the fuzzy-wuzzy school. Although pictorialism was artistic, there were practical reasons for it as well, since negatives at the time weren't very light-sensitive. Photographing someone in soft-focus was much easier on both the subject and the photographer.

Hurrell changed the soft-focus, posed portrait, at least within Hollywood. Partly because of new film and lenses that made it possible to create very sharp images, partly due to his new lighting technique, and partly due to the retouching techniques he adapted for both. Of all three, the lighting was probably the most innovative: Hurrell designed a boom light (like a boom mic, except for lighting) that he could hold and use to highlight the subject from any angle.

Traditionally portrait photographers used three stationary lights to highlight the subject from the front, back, and to shine on the backdrop. Hurrell didn't bother lighting the background, used the boom light to highlight their hair, and then had a reflective surface or another boom light them from below. And because he could move the boom light anywhere he wanted, he could pose the stars wherever he wanted, including the floor (incidentally, photographs of actresses lying on the floor were called "oomph" shots--and if you want to get an idea of what Hurrell's sessions for an oomph shot were like, according to the studio publicity department anyway, all you need to do is watch

this scene from

Blow-Up).

Flexibility with lighting and more light-sensitive film also gave Hurrell the opportunity to abstract his pictures into patterns of light of dark. He refused to let the stars wear foundation make-up while photographing them because he wanted to sculpt their faces with highlights and shadows that make-up flattened out.

Vieira's descriptions of Hurrell's photographic technique are solid and well worth the read if you're interested in photography. Not surprisingly, though, I was left wanting in his analysis of the images. He only briefly touches upon the abstraction that Hurrell was aiming for, and doesn't go into too much depth in placing Hurrell within the broader context of American photography or fine art.

Vieira also argues in some places that Hurrell captured some of the inner emotions and true character of his subjects. But I think in this case he's being torn between admiration for Hurrell and trying to make him appealing given our culture's current obsession with verism. If Hurrell did happen to catch a star's inner character, then I suspect that it was totally by accident and incidental in any event. From the very beginning, what Hurrell was really gifted at was making fantasy

seem like reality. When Ramon Novarro, Hurrell's first celebrity client, showed his series of photographs by Hurrell to his friends, one of them said, "This isn't you, Ramon." That was the point--Novarro wanted to move from silent films to opera because of he was afraid his accent would make him unappealing in 'talkies,' but how to convince people he'd believable as an opera star? The answer was to pose in various operatic roles and have Hurrell photograph him.

And it worked! When Novarro showed the photographs to a studio exec, he was immediately cast in a movie where he could sing four light-opera songs. Likewise, Norma Shearer, Hurrell's next celebrity client, was such a straight-arrow that her own husband didn't believe she could star as a vamp in

The Divorcee, until Hurrell took a series of photographs of her in a silk kimono.

What Hurrell and the studio publicity departments fed the public wasn't reality--it wasn't anything close to reality. Take, for example, this photograph of Joan Crawford before and after retouching. Even taken with my crappy cell phone camera, you can see a dramatic difference in the two images. Before retouching, Crawford has wrinkles, sunspots, and freckles; after retouching, she looks not just twenty years younger, but probably

better than she looked when she was twenty years younger! The Joan Crawford of Hurrell photographs never existed, and the images in his portraits are idealizations, not reality.

In the opening paragraph of this book, Vieira wrote, "Hollywood aped our culture, fed our culture, and to certain extent

was our culture." Considering that, one has to wonder if he's drunk a bit of the glamor koolaid. If he has, one can hardly blame him--

everyone drank the koolaid, even the people who were actually living the reality! Hurrell himself said of pre-War Hollywood, "Those days were like a storybook.... We were the children of the gods." When Cecil Beaton visited Hollywood in 1930, he wrote, "Apollos and Venuses are everywhere. It is as if the whole race of gods had come to California. Walking along the sidewalks... I see classic oval faces that might have sat to Praxiteles. The girls are all bleached and painted with sunburn enamel." Ann Sheridan reflected, "There was a certain kind of fantasy, a certain imagination that is not accepted now. The world is too small."

I think Sheridan has the right of it: pre-War Hollywood was a time and place where the line between fantasy and reality was indistinct, maybe even non-existent, and the pictures--both still and moving--that were based on fantasy were so powerful they produced their own reality. It's said that a picture is worth a thousand words. That may not be true--in fact, photographs often need words in order to make sense--but I do know a picture, no matter how fabricated, is more memorable and convincing than any description in words. The stars of Hurrell's portraits were envisioned as eternally young, beautiful, and ready, and thus that's their enduring image.